- Update #2: Complete Manuscript

- Update #3: Revisions Complete

- Update #4: Production and Copyediting

- Update #5: Cover Reveal, Pub Date, and Page Proofs

So that book I'm writing!

Currently, I have over 80,000 draft words and notes (including the sample chapters I submitted with the proposal). This is a milestone because the manuscript goal is 80,000 words.

However, these 80,000 words are first draft words, not submission-ready words. They are only loosely lumped into chapters, not fully organized or structured. They are my reading notes, my thoughts and ideas, paragraphs that don't flow together yet, comments about statistics I need to look up, facts I need to verify, and references I need to track down. In short, it's all the raw content that will be able to be shaped into a book.

For those curious about mechanics, I have logged the majority of these words from my phone (I mostly use voice typing). I sit at the kitchen table taking notes while the kids eat breakfast. I add a few words from the floor in our playroom while the kids build with Legos. A couple hundred words a day adds up fast.

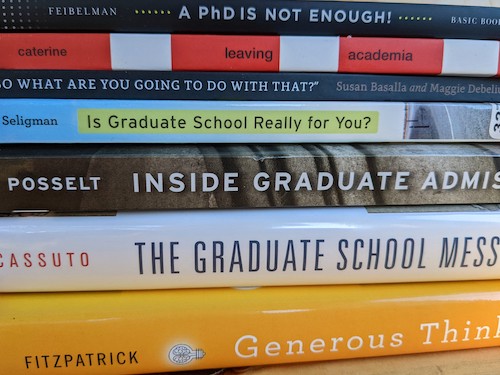

In my research for the book, I've read existing books on getting through graduate school, such as:

- Jennifer Calarco: A Field Guide to Graduate School

- Amanda I. Seligman: Is Graduate School Really For You?

- Peter J Feibelman: A PhD Is Not Enough! A Guide to Survival in Science

I'm reading books about non-academic career paths, including:

- Susan Basalla and Maggie Debelius: So What Are You Going to Do with That? Finding Careers Outside Academia

- Christopher L. Caterine: Leaving Academia: A Practical Guide

I'm reading books about issues in graduate education, such as:

- Julie R. Posselt: Inside Graduate Admissions

- Leonard Cassuto: The Graduate School Mess: What Caused It and How We Can Fix It

- Kathleen Fitzpatrick: Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University

I've also been reading nonfiction books that aren't specifically about graduate school, but are nonetheless highly relevant to thriving and making the most of your education and your life, such as:

- Daniel H. Pink: Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

- Bill Burnett and Dave Evans: Designing Your Life: How To Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life (Read my review!)

- Adam Grant: Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

I have more to read and research, of course—there's always more to read and research.

But as another student in graduate school told me once, at some point, you have to stop reading and start creating. You have to turn everything you know into something.

That's the point I'm at now. And honestly? Revision is the fun part.

Revision is where the magic happens. Revision is when I make the words flow. It's when ideas become coherent. It's when I hunt down that quote from that book I read two years ago that would be perfect to mention in this section, add references, rearrange content, and generally improve the coherency and structure of my words.

Revision is not a one-time process. It's not write, revise, done. It's write, rewrite, reword, rearrange, revise, repeat. Revision is what I'll be doing on the book for the next six months.

Unfortunately, revision is harder to do on my phone. I need more office time with a proper keyboard and monitor. So I've switched from having a daily book word count to having a daily book time count. This will be easier and easier to schedule as the weather warms up—I'll send everyone else outside while I get my quiet writing time in!

Making progress. I'll keep you updated!

This post first appeared on The Deliberate Owl.